On April 26, 2020 г. Rossiya-1 TV Channel observer Dmitry Kiselyov listed Russian historical figures who he believed deserved a monument in Russia. Among others, he mentioned Pyotr Krasnov, a Cossack chieftain and an active Nazi collaborator during WWII. Later, Kiselyov, one of the most notable Russian media figures, disavowed his statement saying that he had mentioned Krasnov’s name ”just in case”. However, for a number of reasons, a slip of the tongue like that is not easy to forget.

Since the preparation of a TV show always implies teamwork, it is rather strange that no one at Rossiya-1 bothered to prevent the anchorman from making the blunder. What is more important is that, in recent decades, we have seen multiple attempts to rehabilitate and commemorate those involved in collaboration with Nazis. The most notorious example was the 2016 initiative of the Russian War History Society to inaugurate a memorial plate in St.Petersburg dedicated to the Finnish Marshall Gustaf Mannerheim. The civil society was angered at the fact that St.Petersburg was paying tribute to the enemy who laid siege to the city (then Leningrad) and was responsible for terror against non-Finnish population in occupied Karelia from 1941 till 1944. Only after a wave of protests the plate was dismantled, though not destroyed but moved to the First World War museum in Tsarskoye Selo.

Concealing pro-Nazi sentiments of such famous Russian émigrés as Great Prince Vladimir, philosopher Ivan Ilyin, chess player Alexander Alekhine, writers Dmitry Merezhkovsky and Zinaida Gippius, has long become a tradition in journalist and academic writings. The fact that those people flirted with Nazism tends to be represented as just an episode in life, a passing fancy, or something that goes in line with the person’s anti-Bolshevik struggle.

Since the early 1990s, Russia has seen many attempts to rehabilitate and commemorate Pyotr Krasnov. No one tried to hide the real reasons behind them. According to Leonid Lamm, head of the Volunteer Corps organization, “today, the Cossack organizations, multiple in number but yet divided, do not have another remarkable icon, another symbol of anti-Bolshevik resistance to unite behind. All other Cossack chieftains pale in comparison with General Krasnov, extradited by Englishmen and executed by Bolsheviks, so his rehabilitation has to be a sign of an ultimate victory over the official Bolshevik historiosophy.”

In 1994, a memorial plate to Krasnov and other Cossack collaborationist generals was set up on the territory of the Moscow All-Saints church. That monument was destroyed by unidentified person, but in 2006, another monument to Krasnov made of bronze was installed in the estate of businessmen Vladimir Melikhov, located in Yelanskaya, Sholokhov District, Rostov Region. Despite multiple requests of MPs and public organizations, the monument remained intact, except for the deleted inscription telling whom this monument was dedicated to. In January of 2008, Victor Vodolatsky, a member of the ruling United Russia party and a State Duma MP, initiated a workgroup on Pyotr Krasnov rehabilitation. However, this initiative was predictably met with protest and blocked.

The legal and moral rehabilitation of Pyotr Krasnov faces insurmountable difficulties nowadays. While the pre-1917 Krasnov’s image, more or less, falls under the template of a faithful Tsarist servant and a father to his men, his actions after the February Revolution raise wide criticism, not only from the standpoint of the Soviet historiography.

In 1917, Krasnov did not hesitate to start serving the Russian Provisional Government, but soon took part in the Kornilov affair against the new republican authorities. In October 1917, Gen. Krasnov was moving his troops toward Petrograd against the Bolsheviks, got captured and then freed, after giving an officer’s word of honor that he was not going to fight against Soviet Power.

Like many antirevolutionary officers, Krasnov broke his promise, which did a lot of harm to the White movement since the Red decided to rely on bullets rather than words of honor. In the meantime, the general fled to the Don where he was elected chieftain of Don Cossackdom and started a war against… Russians. Krasnov himself believed that “the war against the Bolsheviks in the Don region has turned into a people’s war, a national war rather than political or class war”1.

A part of that war were the following Krasnov’s requests directed to German Emperor Wilhelm II:

1) the recognition of the Almighty Don Host as a rightful autonomous entity and, in the process of liberating the Kuban Host, the Astrakhan Host, the Terek Host and the peoples of the North Caucasus, a bigger merger with the Don Host, under the name of the Don-Caucasus Union;

2) assist the accession of Kamyshin and Tsaritsyn (Saratov Governorate), Voronezh, as well as Liski and Povorino stations;

3) issue an order that would make Soviet Mosсow leave the territory of the Almighty Don Host and other countries that were going to join the Don-Caucasus Union, and “make Soviet Russia reimburse all the losses from the Bolshevik invasion”2.

It is no surprise that Krasnov’s requests were accepted by Germans, and it was the collapse of the German Empire that prevented Pyotr Krasnov from becoming a founding father of a new state. In February 1919 Entente-oriented Anton Denikin insisted that Krasnov resigned and left Russia.

After emigration, Pyotr Krasnov became a German citizen. He was heavily involved in literary activity and heartily supported the Nazi regime when it came to power. In his 1939 novel, “The Lie”, Krasnov fully identified his characters with the Third Reich:

“Lisa was right in her severe judgment: Russia was no more. She did not have a Motherland or her own. However, when the Bremen floated noiselessly by and she saw a black swastika in a white circle on a scarlet banner, a sign of eternal motion and continuum, she was feeling a warm tide covering her heart… That’s Motherland!”3.

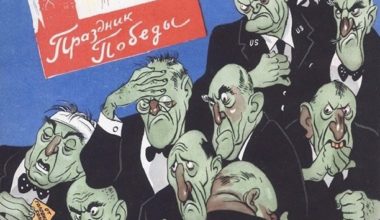

On June 22, 1941, Pyotr Krasnov fully supported the Third Reich invasion against the Soviet Union. In his public address, he stated: “Tell all the cossacks that this is no war against Russia, but rather against Communists, Jews and their henchmen who sell Russian blood. May God help the German sword and Hitler! Let them accomplish their endeavour, similar to what the Russians and Emperor Alexander I did for Prussia in 1813”4.

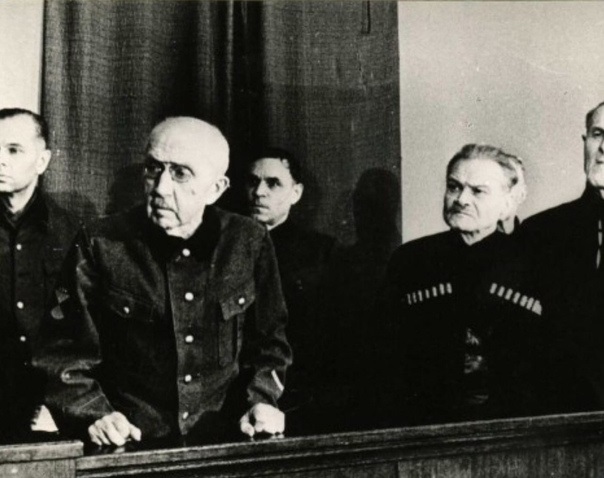

Starting from September 1943 till the time of his arrest in May 1945, Krasnov was head of the Main Directorate of Cossack forces of the Reich Ministry for the Occupied Eastern Territories. After Hitler’s defeat, Krasnov was captured by the English, delivered to Soviet government, brought before the court of law and sentenced to death by hanging on January 16, 1947. The sentence was implemented on the same day.

The aforementioned facts leave no chance to legitimize the efforts to rehabilitate Krasnov, who was not only the enemy of our country in WWII, but also a committed pro-Nazi anti-Semite and a symbol of Cossack separatism, disrupting the integrity of the Russian Federation. For some influential political and public figures, however, Krasnov’s anti-Bolshevik sentiments matter more than all of his crimes. The main goal behind Krasnov’s rehabilitation is no secret. It is an effort to revise Civil War results and to glorify the Russian equivalent of Gen. Franco or Mannerheim.

Moreover, the decision to rehabilitate Krasnov, or Vlasov, or other Nazi collaborators would lead to a total revision of the 1941—45 war history, portraying it like a “second Civil War” and equalizing Soviet soldiers with those who sided with the Reich. The concept of a ‘prolonged’ civil war in the first half of the 20th century has long been discussed by both foreign and Russian historians. The Hitlerite invasion intensified national, class and social differences in a number of European countries, including Greece, Yougoslavia, Poland and Italy. No wonder that similar processes took place on Soviet territories. Conservative, nationalist, and far-right groups saw the 22th of June, 1941 as a chance to have revenge for the defeat of 1917—1921, but this is no excuse for the Third Reich collaborators. Their cooperation with Hitler only lead to their decades-long political and public de-legitimization, and there is no reason to change that status quo.

The idea of “reconciliation” with the far-right and pro-fascist groups from the Russian past is also dangerous for the present. As historical experience shows, when one tries to set control over, or flirt with, the far-right, one cannot stop them from slipping the leash.

ReFERENCES:

- Галин В. Тенденции. Интервенция и гражданская война, М., 2004. С. 148

- Краснов П.Н. Всевеликое войско Донское // Архив русской революции. Берлин, 1922. Т.5.

- Краснов П. Ложь, М., 2013. C. 7

- Голдин В.И. Роковой выбор: русское военное зарубежье в годы Второй мировой войны. Архангельск; Мурманск, 2005. С. 244.