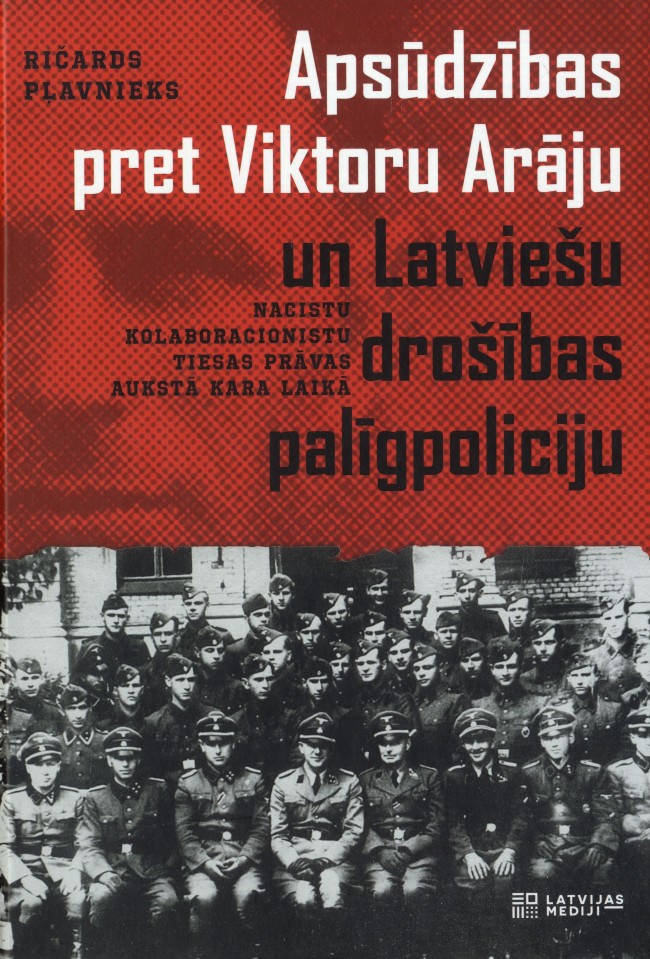

A book by a Latvian-born American historian Richards Plavnieks, “The Cases against Viktors Arâjs and the Latvian Auxiliary Police”, recently published in Riga, contains a remarkable story which, to my mind, deserves to be turned into a movie.

The title of the book tells exactly what it is about: the notorious Arajs Kommando that killed tens of thousands of unarmed people during the war, including Jews, Roma, local communists, Soviet PoWs, patients at mental health clinics.

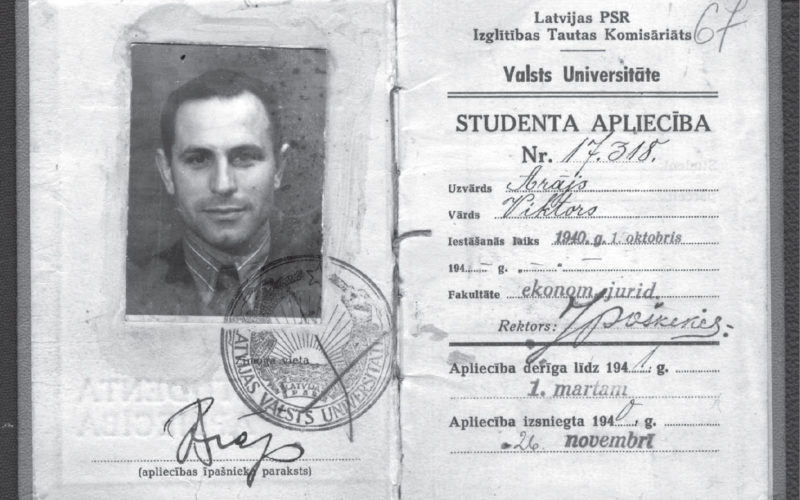

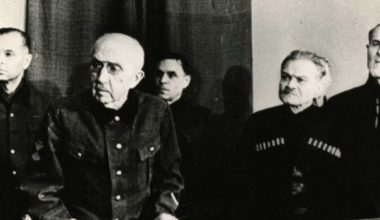

Viktors Arajs, founder and leader of the criminal punitive squad, used to hide himself in West Germany after the war, living under his wife’s last name. It was only in 1975 that he was arrested by German police, and, after four years, he was sentenced to life in prison. In 1988, Arajs died in the local prison in Kassel, West Germany.

One remarkable thing is that Arajs used to have all chances to evade justice and die in his bed. In the early 1960s, German law enforcement agencies almost gave up on their failing attempts to find him. They were about to stop the search, his long forsaken file lost somewhere on dusty archive shelves.

Arajs was almost guaranteed such a happy (for him, of course) outcome, when a man with a reputation of some kind of a local idiot ruined his game. The man was an odd one and even called himself ‘mentally crippled’. His name was Janis Eduards Zirnis.

“Nazi hunter”

The author of the book only managed to draw a vague image of Zirnis and his life. There are lots of blank spots in the character’s back story. It is a well-established fact that he was in Arajs’ Kommando from March till October of 1942. He quit as he did not want to participate in mass shootings. Later he told that he had joined the squad as a “secret agent of the Resistance”, and even managed to form an underground anti-Fascist group of 30 men. These seem nothing but his flight of fancy, though.

In 1943, occupation authorities arrested Zirnis, suspecting he has sympathetic view toward Bolshevism. He spent over a year in the Riga central prison where he was tortured. However, finally they released him, maybe because they saw he was no conspirator but just an air-monger, acting on his own.

Not long before the Red Army liberated Latvia, the mass exodus of population brought Zirnis to the West. There, in West Germany, among other Latvian refugees, Zirnis decided he would play the role of a Nazi hunter. He appealed to Latvian migrants, asking them to repent and disclose their war criminals. “Latvians, who at least have a grain of honor and self-consciousness left, must expose their war criminals that are still free […] Dirty deeds of those men made Latvian honor and morals tainted,” he wrote in one of his addresses.

Zirnis tried to co-operate with West German law enforcement agencies engaged in the search of former Nazis. However, no one was taking him seriously – and not without reason.

Indeed, who would believe a person claiming he was in the anti-Hitler resistance together with Willy Brandt – future German prime minister? Or the one who shared “confidential” information on war criminals which, in reality, he took from published books and booklets?

Zirnis founded a lot of organizations under pretentious names, e.g. “the Federation of Nazi Victims in Baden-Wuertemberg” or “the Baltic Center for Documenting Resistance Fighters and Victims of Fascism”, and then signed his letters on behalf of those. A closer look into the organizations showed that Zirnis was their only member…

It is clear that Zirnis sincerely wanted to be useful, be a hero, as well as punish his compatriots for joining the Nazis and clear the reputation of Latvia. However, in his addled mind he mixed fact and fiction, wish and reality, in a Quixotic cocktail that no one wanted to taste.

How the Nazi butcher failed to die in his bed

In 1973, the prosecutor of Stuttgart received two letters. The letters said that Sturmbannfuehrer Viktors Arajs was killed on German territory by a Soviet secret service. The message was in the first person, as if the authors were those who committed the punitive act (here I will quote the author of the book):

“No more fear for the mass murderer Viktors Arajs […] Our special-purpose squad killed him on January 19, 1973. No one will ever find him. He is neither first, nor last. We have a long list of war criminals at our disposal. We are even going to take some of them to Riga.“

Only a meticulous German official could take such a text in full seriousness, although its style clearly reminded of criminal stories for kids (one catch phrase was probably missing, “We have long arms”). Moreover, Janis Eduards Zirnis was the sender, claiming that he had got the letters from an undisclosed person. To my mind, the style of the two letters unmistakably gives the author away.

However, the letters gave momentum to the squeaky wheels of German bureaucracy, and they started rolling. One could not simply ignore, or get rid of, the information received, for it was related, firstly, to homicide, and, secondly, to an armed Soviet group operating in West Germany.

Instantly, one had in mind the case of Herberts Cukurs, who was Arajs’ partner in crime, captured by the Israelis. Could it be that the KGB followed Mossad’s lead and assassinated Arajs – who knows? Speculations like that were quite possible in the German political elite at that time.

Anyway, the Arajs case was reopened and prioritized, with an enterprising Hamburg prosecutor, Lothar Klemm, put in charge of the investigation. At that time, Klemm had already been credited with several successful trials over Nazis.

Klemm got down to business rather thoroughly. Digging through old criminal files, he came across a piece of evidence telling that Arajs was living in Frankfurt under his wife’s maiden name. The witness said he just quoted the rumors that were circulating around him – that was probably the reason why no one had took the evidence into account at that time and let the file gather dust on an archive shelf.

Shortly after Klemm ordered the police to carry out an inquiry, they found and arrested Arajs. He was left no chance to die in his own bed.

No one, at least the author of the book, knows what happened to Zirnis after that. In a recent interview, he once again stressed that, if it were not for Zirnis and his obsession with Nazi hunt, the Arajs case would have no chance to be revised.

There seems to be some message from higher forces in this story, or at least a lesson. It may say that sometimes even a blessed fool can bring Justice to this world.

Published at: lv.baltnews.com. Reprinted by permission of the author.